One Proof the Universe Had a Beginning

From PBS.org

Bell Labs built a giant antenna in Holmdel, New Jersey, in 1960. It was part of a very early satellite transmission system called Echo. By collecting and amplifying weak radio signals bounced off large metallic balloons high in the atmosphere, it could send signals across long distances. Within a few years, the Telstar satellite was launched. It had built-in transponders and made the Echo system obsolete.

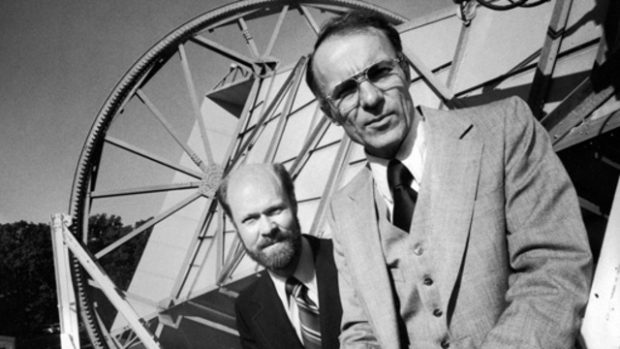

Meanwhile, two employees of Bell Labs had had their eye on the antenna. Arno Penzias (b. 1933), a German-born radio astronomer, joined Bell Labs in 1958. He had done his PhD on using masers (microwave amplification by stimulated emission of radiation) to amplify and measure radio signals from the spaces between galaxies. He knew the Holmdel antenna would also make a great radio telescope and was dying to use it to continue his observations, but he pursued other research while the antenna was booked for commercial use. Another radio astronomer came to Bell Labs in 1962 with the same idea. Robert Wilson (b. 1936) had also used masers to amplify weak signals in mapping radio signals from the Milky Way. The launch of Telstar in 1962 gave both researchers what they wanted: the Holmdel antenna was freed up for pure research.

When they began to use it as a telescope they found there was a background “noise” (like static in a radio). This annoyance was a uniform signal in the microwave range, seeming to come from all directions. Everyone assumed it came from the telescope itself, which was not unusual. It hadn’t interfered with the Echo system but Penzias and Wilson had to get rid of it to make the observations they planned. They checked everything to rule out the source of the excess radiation. They pointed the antenna right at New York City — it wasn’t urban interference. It wasn’t radiation from our galaxy or extraterrestrial radio sources. It wasn’t even the pigeons living in the big, horn-shaped antenna. Penzias and Wilson kicked them out and swept out all their droppings. The source remained the same through four seasons, so it couldn’t have come from the solar system or even from a 1962 above-ground nuclear test, because in a year that fallout would have shown a decrease. They had to conclude it was not the machine and it was not random noise causing the radiation.

Penzias and Wilson began looking for theoretical explanations. Around the same time, Robert Dicke (1916-1997) at nearby Princeton University had been pursuing theories about the big bang. He had elaborated on existing theory to suggest that if there had been a big bang, the residue of the explosion should by now take the form of a low-level background radiation throughout the universe. Dicke was looking for evidence of this theory when Penzias and Wilson got in touch with his lab. He shared his theoretical work with them, even as he resignedly said to his fellow-researchers, “We’ve been scooped.”

Ironically, Robert Wilson had been trained in steady state theory (which suggested the universe was without beginning or end, unlike big bang theory), and he felt uncomfortable with the big bang explanation of their radio noise. When he and Penzias jointly published their research with Dicke, the Bell Lab researchers stuck to “just the facts” — simply reporting their recorded observations.

It is ironic, too, that many researchers — both theoretical and experimental — had stumbled on this phenomenon before, but either discounted it or never put it all together. This was partly because, as Steven Weinberg wrote, “in the 1950s, the study of the early universe was widely regarded as not the sort of thing to which a respectable scientist would devote his time.” Since Penzias, Wilson, and Dicke’s work, all that has changed. The measurement of cosmic background radiation (as the Holmdel telescope’s noise is now called), combined with Edwin Hubble’s much earlier finding that the galaxies are rushing away, makes a strong case for the big bang. By the mid 1970s, astronomers called it “the standard model.” Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson received the Nobel Prize in physics in 1978.